Before a performance is polished, premiered, or reviewed, it exists in a more vulnerable state. What happens when you invite audiences into that space?

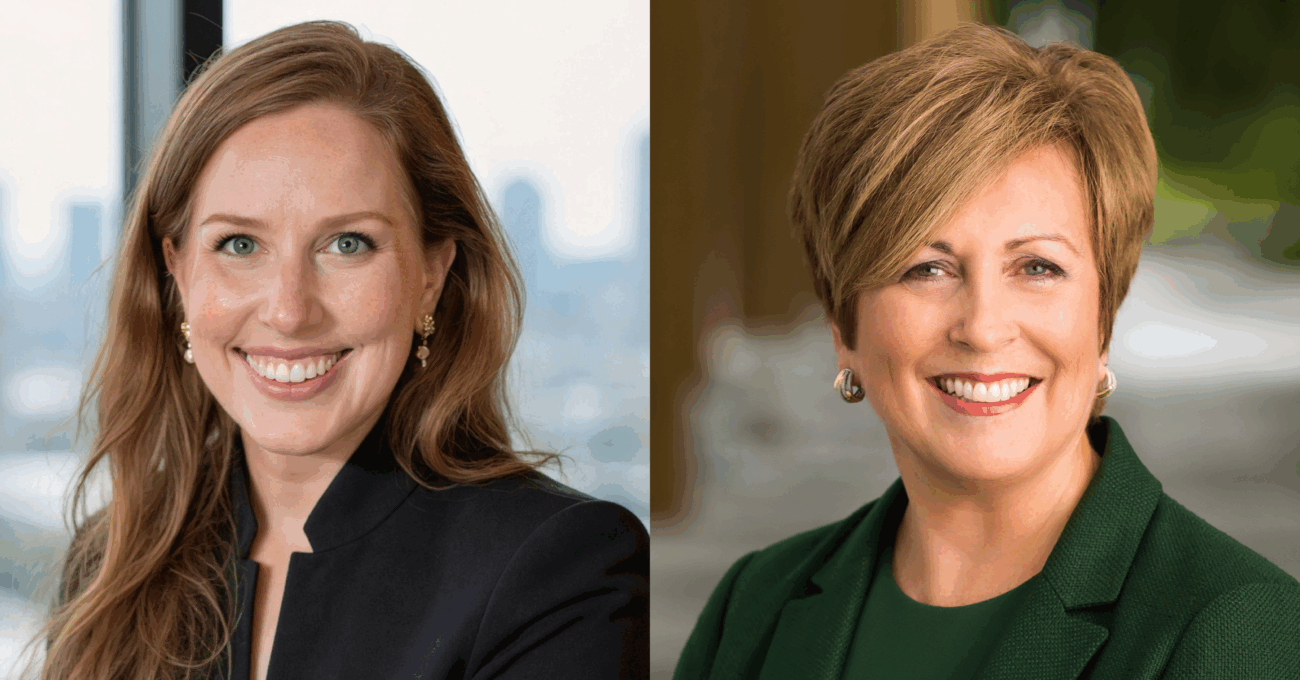

As Executive Director of Works & Process, Duke Dang leads an organization built around that idea. By welcoming audiences into the rehearsal room—where new work is tested and shaped—Works & Process transforms performance from a finished product into a shared journey.

Under Duke’s leadership, the organization has grown in scale and influence, setting the standard for how institutions can nurture artists at pivotal moments in their development. In this episode, Duke reflects on building sustainable pathways for artists across disciplines, creating space for artistic risk, and deepening audience investment in new work.