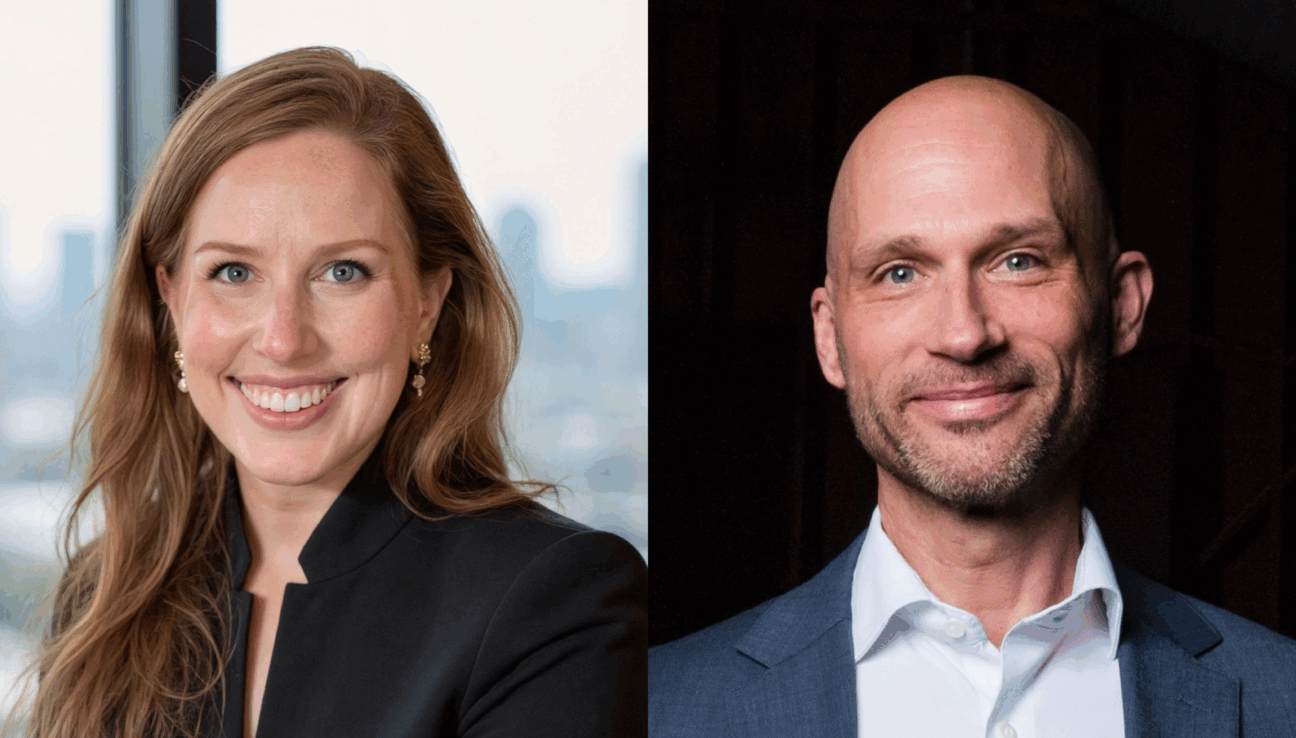

It’s Boot Camp week! In this special mini episode, Capacity’s President Christopher Williams joins host Monica Holt to pull back the curtain on Boot Camp, the leading conference for arts and culture professionals. They dive into how this year’s program came together, the sessions they’re most excited about, and how courage and curiosity are the keys to a stronger sector.